Covid and the Map

Having loved the first exhibition in Rua Red’s Magdalene series, we made plans for a Wild Gees trip to see the next one, The Map by artists Alice Maher and Rachel Fallon, as soon as it opened. The fact that the collaboration also featured a ‘sound response’ by writer Sinéad Gleeson (who we encountered on our Sligo adventure) was an added incentive, as if we needed one. So we planned, and Covid laughed.

One of us, who lives nearby, managed to see The Map early but to get all three of us in Dublin and not actively Covid-y proved a challenge as we entered yet another wave. It began to seem that we wouldn’t get there before the exhibition closed at the end of January. Then a reprieve, The Map was extended until International Women’s Day. How fitting, and how fortuitous for us. Another plan was hatched, this time to coincide with one of our birthdays, a three-day weekend of catching up, celebrating and Wild Gees-ing together, at last. Then the day before, just before the country collectively threw off the yoke of mask-wearing completely, the last of us (smugly) standing was a close contact. We decided not to risk the sleepover or the car journeys together but a compromise was reached. Wearing our mega-masks (FFP2) we met up outside Rua Red in Tallaght and took turns to go in and view The Map when the gallery was empty.

That there were times the gallery was empty on the last Saturday before the exhibition closed is a sin. The Map deserves to have been mobbed, though we’re selfishly glad it wasn’t as we wouldn’t have risked mixing in a crowd. One of us had the privilege of viewing it several times, and discovering something new in it each time, the other two were raging we never got that chance as it deserved time and thought to take it all in.

As you enter the gallery, the map has its back to you. With the lights behind it, the effect is of an ultrasound image. Circling round, the first impression is the sheer scale of the thing, hanging from the ceiling and dominating the large, otherwise empty, space. So tall is it, that it’s difficult to make out or even photograph some of the elements near the top. Approaching it, the detail emerges and the awareness of the craft and the labour that has gone into creating this map of misogyny. The artists, Alice Maher and Rachel Fallon, worked on it for more than two years. The hand-embroidered land masses and bodies of water are not recognisable as Ireland as a geographical entity, but they are too horribly familiar as a female history and experience of life here.

WInd of Change

Tá

Repeal

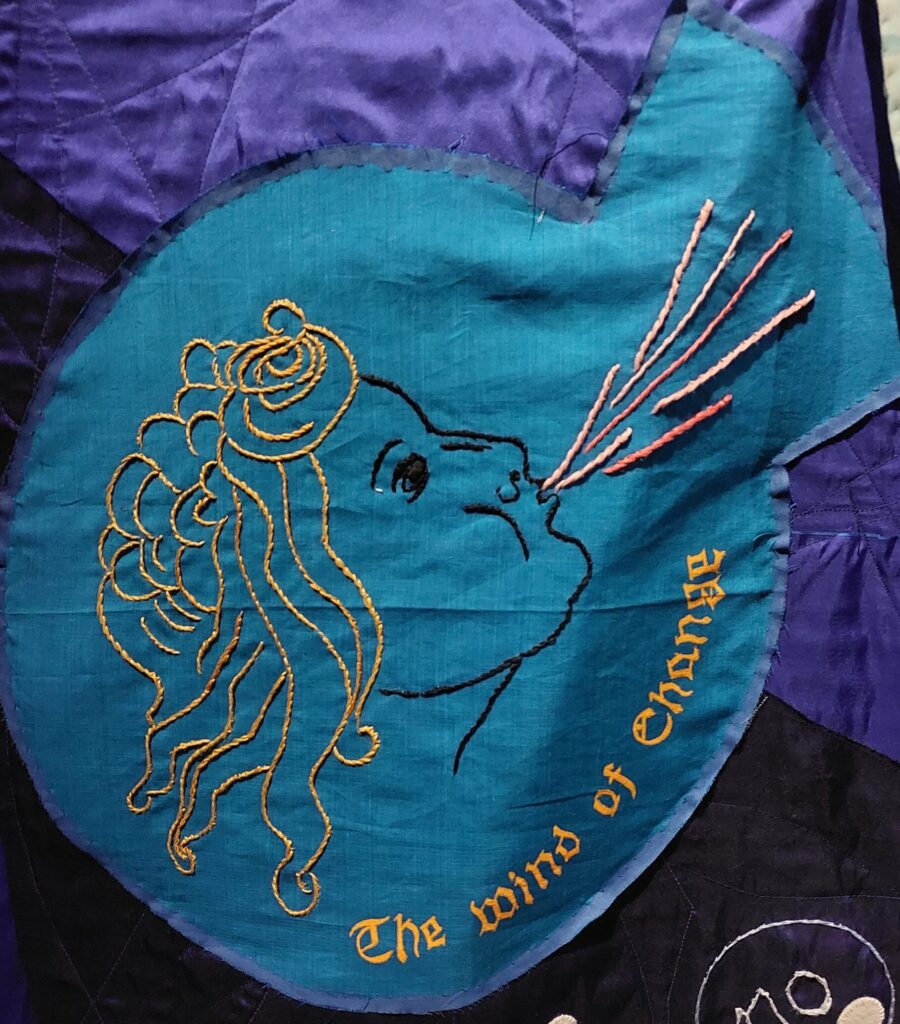

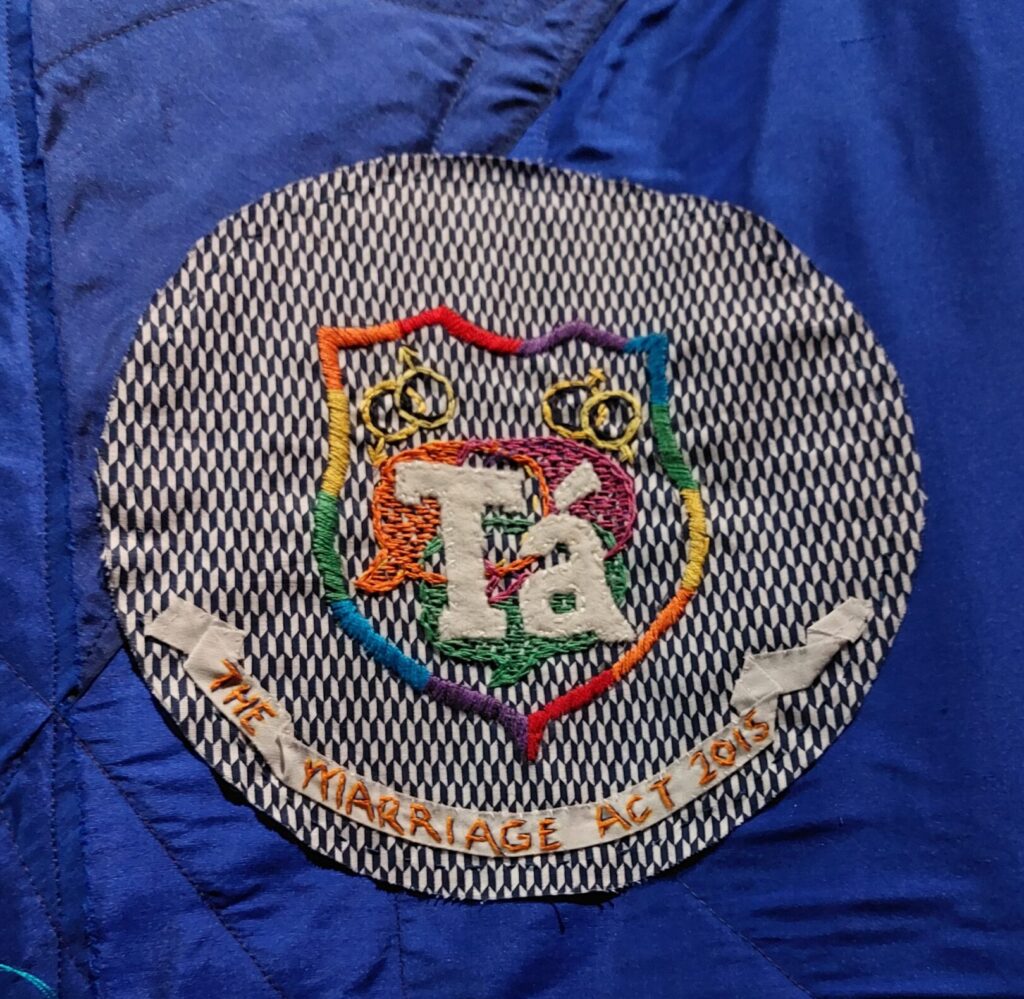

Each of us came away with something different, but we were all struck by the winds that appear in the four corners. One of these was of change and around it are recent pieces of legislation that have changed women’s lives for the better, The Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy Act 2018, The Marriage Act 2015, but the other winds carried too many laws over too long a period that sought to limit freedoms on this island. The map is a cartographic representation of the institutionalisation and incarceration of women (following the series theme of Mary Magdalene myths and legacy) in our country’s history.

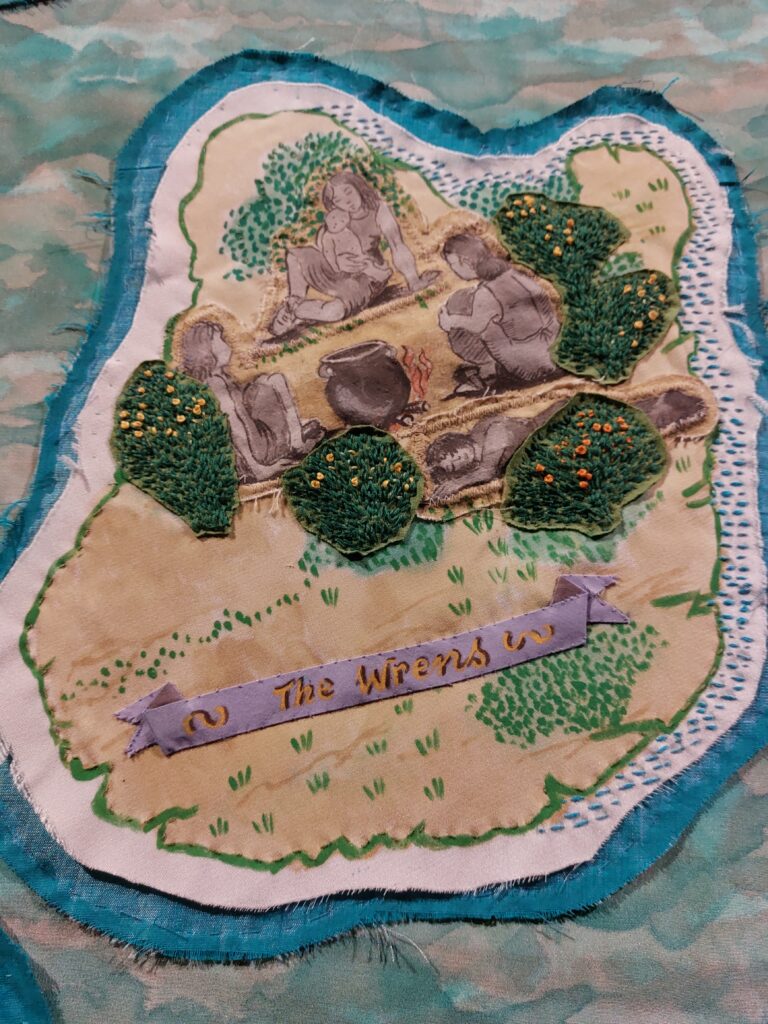

Our gazing at the map is accompanied by Sinéad Gleeson’s audio, which plays on a loop in the smaller gallery space. In hindsight, it would have been interesting to experience this first, approaching the map with a tour guide of sorts, but we all chose to engage with the map visually first. There is so much to see! The Currragh wrens make an appearance on one island, a nod to the first exhibition in the series They Come Now, The Birds. The wrens and many other women were incarcerated by the Infectious Diseases Acts, which held women in ‘lock hospitals’ against their will and treated them for the sexually transmitted diseases that continued to be spread by the men who had infected them. But there isn’t time to be outraged at this when there are so many injustices to take in. That the map is so visually beautiful and what its topography represents so rage-inducing is what makes this experience so powerful.

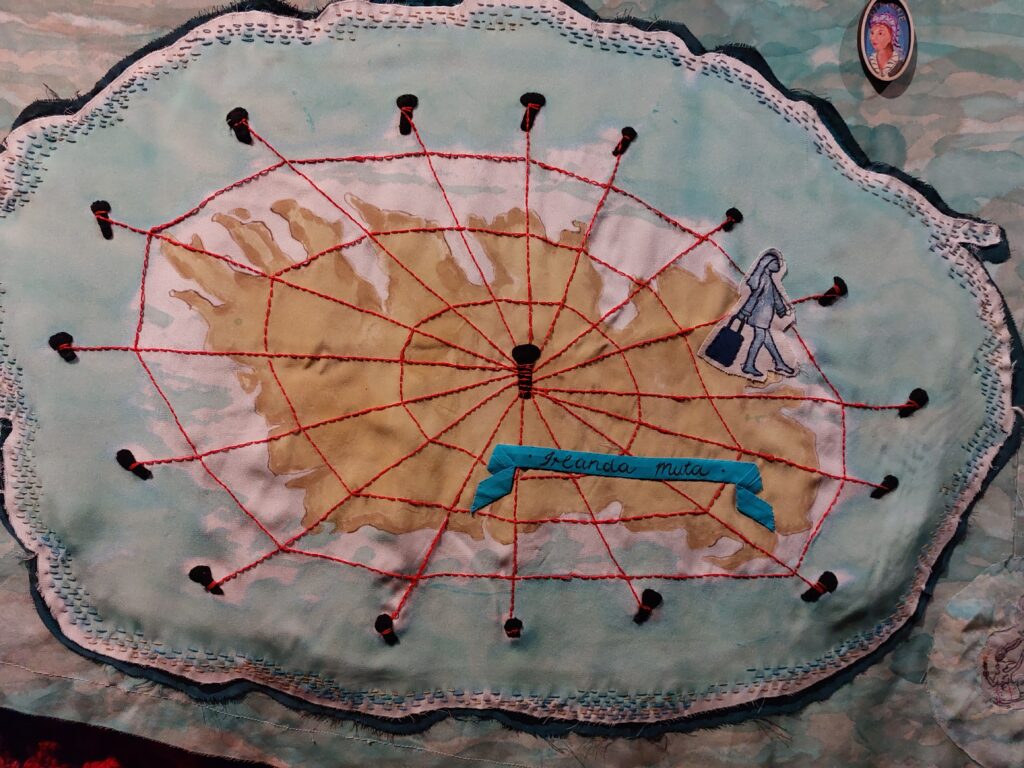

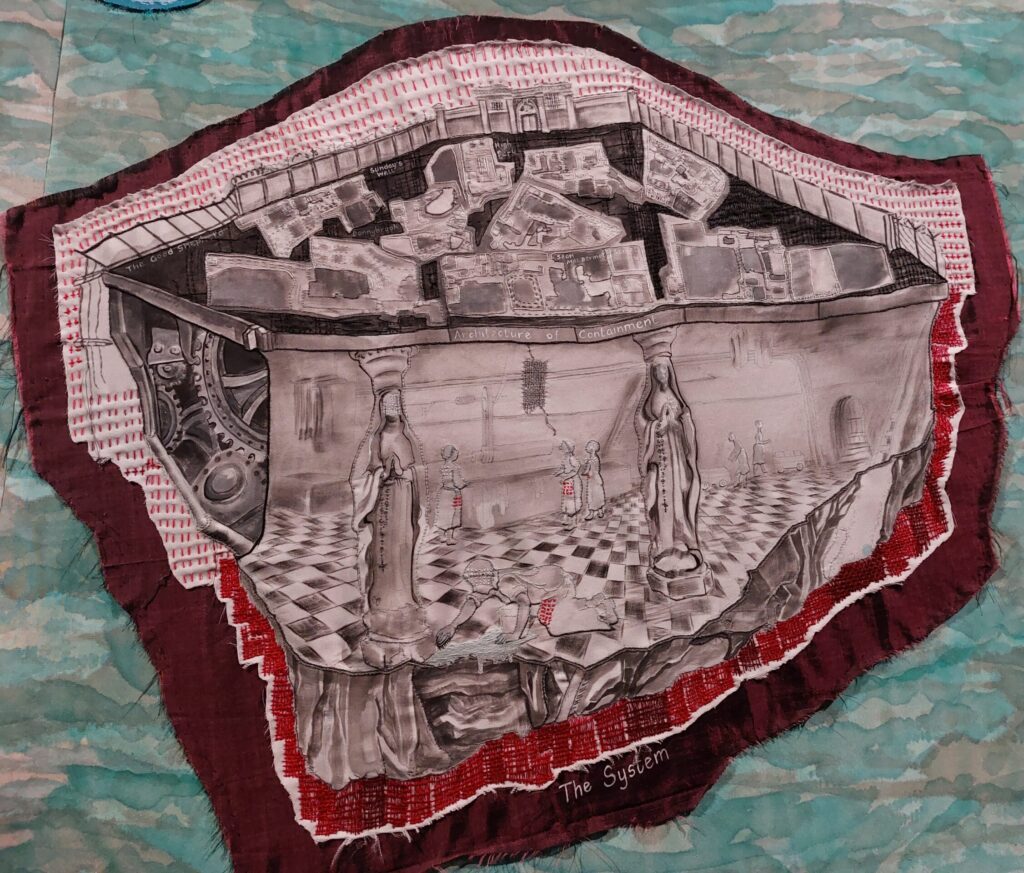

The constellation of the Little Sinner depicts a pregnant girl, so villified in Irish society while the men who impregnated her faced no punishment or stigma. The Mother and Baby Homes and Magdalene Laundries in which these girls and women were incarcerated are captured in the Architecture of Containment, where girls scrub the floors of a crumbling edifice held up by statues of the Virgin Mary. The Big Sinner is the single mother with a baby and toddler in tow. In the Channel of Tears, a Cillín holds the bodies of the unbaptised babies the Church refused to bury. The streets of Slag Island are named for the wanton women of many traditions, Jezebel, Medea, Salomé, as well as the contemporary Slut Walk. The large, sprawling Land of the Law, is stitched with extracts of legislation that has sought to criminalise us and limit our rights, the constitution that said we were all equal before the law, then awarded rights to foetuses that trumped our right to life. Irlanda Muta features a woman with a suitcase, leaving the net that covers the island, presumably to access reproductive health services elsewhere. In the water, the monsters of poverty and injustice raise their heads.

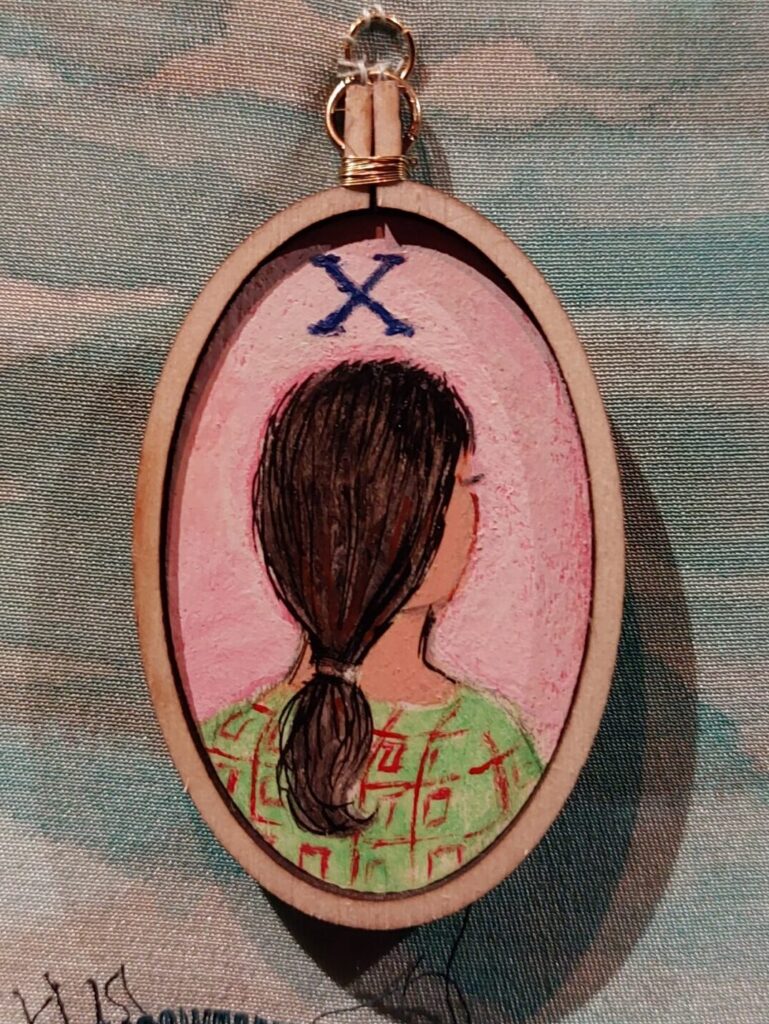

And yet, the map invites us to imagine. What if we were not trapped in Heterotopia or Cisopolis? In Metamophopolis (no, you try to pronounce it) there is the possibility for change. The map is scattered with cameos of women who have instigated progress here and abroad: Bernadette Devlin, Mother Jones, Marsha P. Johnson, Rosa Parks, Nan Joyce, Miss X (though in Savita’s case, this change was at the cost of her life), and strong female figures from mythology such as Maebh, Gráinne and Brigid. A Sheela-na-Gig defiantly flashes her vulva, sharing an island with an anthropomorphic vulva going for a walk. A Mergig is surely celebrating her gender-affirming genitals. On Bloody Foreland, volcano breasts erupt with milk. There is hope here.

And so, to the small dark room and Gleeson’s hypnotising tones. One of us chose to lie down on the bench with her eyes closed, only to be sat on by an unsuspecting man who wandered in to an apparently empty room. The others sensibly remained seated but closing your eyes is the only way to experience this immersive sound response. It begins with ‘I am…’ and lists the women from the map, then BAM “I am the first first child they put in the septic tank”. It is nigh on impossible to experience this and not cry. It articulates the themes of the map in a visceral way. Gleeson takes us on a tour of the map, starting on Slag Island visiting the pit girls, then the syphillis girls in the lock hospital, the “land of labour” in Lillith’s Garden, Ráth na Marbh where “bombs go off in women’s bodies all the time”, Banshee villages “filled with the sound of women wailing; not as augury, but for all they’ve lost”, in Coventown “we burn it all down and chant until dawn”, in Slutside “we march with our banners”, finally, in the Imaginal Forest, we “gather our paper from witch-armed trees” and “keep writing our histories in contour lines”.

“We are the map” she says, followed by an echo of voices. “We are the map” says Chiamaka-Enyi, says Amanda, says Rachel, says Felicia, says Rosaleen… Each of us stays in the room for some time after the audio finishes, hot tears spilling down our faces.

Because of Covid, we can’t urge you to see this incredible exhibition before it ends. Three days later, the virus felled the last third of the Wild Gees. The writerly third. Hence our blog post is weeks late, having been left with such a profound tiredness there was nothing left after work and sleep for weeks. We can add our voices to those that say The Map deserves a permanent home (we’re looking at you, Collins Barracks). We can also say that given the calibre of the series so far, the next Magdalene exhibition is sure to be amazing. The Tower by Jesse Jones opens on 27 May. We are making our plans now, but in a low voice so Covid doesn’t hear.