Cashel of the Sheelas and the friendly folk

According to the ever-handy online map of Sheela na Gigs, there are at least three proper Sheelas in Cashel, where we base ourselves for a flying visit.* We are soon to discover that there are some fake Sheelas as well, and they all have their charms. However, the first thing we notice about Cashel (apart from the Rock obviously, which is too impressive to miss) is how friendly it is. For Sale signs say ‘sorry it’s gone’ instead of ‘sold’. At a No Exit onto a busy road, the sign reads ‘turn back you’re too beautiful’. Every time we even think about crossing the road a car stops, the driver smiles and waves us across. Every time! Cashel must have the friendliest drivers anywhere.

Our first stop is the GPA Bolton Library in the grounds of the Church of Ireland Cathedral. There’s a beautiful gatehouse covered in flowers and looking very much inhabited but the library building is locked and the Sheela inside isn’t accessible. The map suggests the tourist office on Main Street has the key but they don’t. They tell us the Library’s collection has been moved to the University of Limerick due to a damp problem and no one is quite sure if the Sheela is still inside or has been moved as well. We do however meet another guardian.

Sam outlines his theory that the Sheelas were intended to be androgynous, with both male and female features. A medieval trans or non-binary Sheela is a new and intriguing variation in Sheela theories.

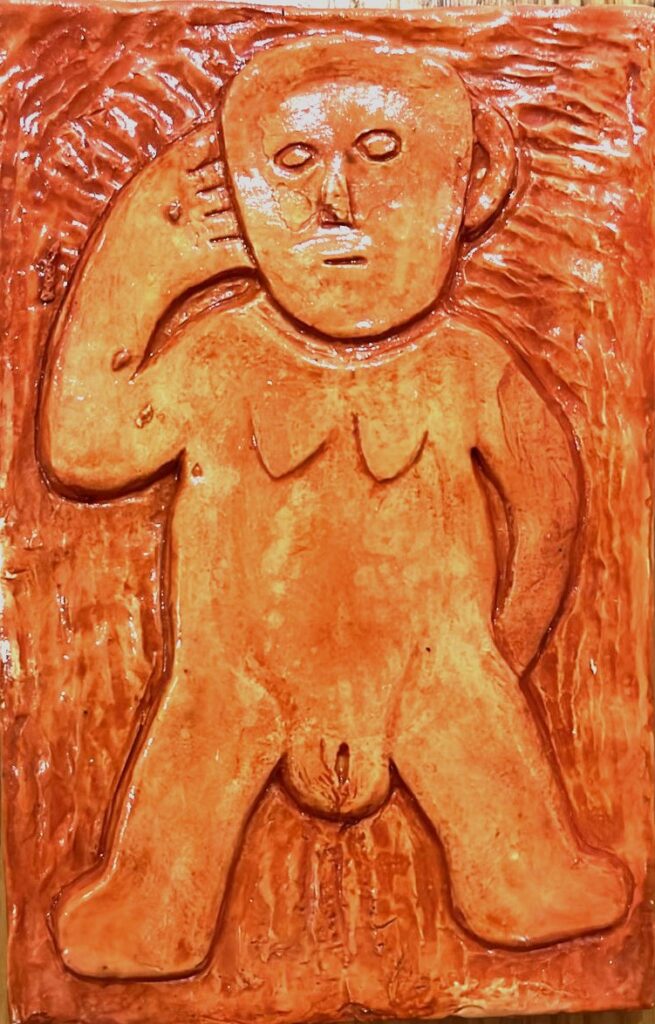

Despite having only worked at the tourist office since January, Sam knows all there is to know about Tipperary’s Sheelas. On Jack Roberts’ map of Sheela-na-Gigs (on sale in the tourist office), he shows us the Rochestown Sheela, one of the first to be recorded, which has been stolen and is likely in a private collection. The tourist office also stocks gorgeous ceramic replica Sheelas (also by Jack Roberts of Bandia Design), including our favorite from Behy. We may have bought a couple. With the Ballinderry Sheela (below, centre) as an example, Sam outlines his theory that the Sheelas were intended to be androgynous, with both male and female features. A medieval trans or non-binary Sheela is a new and intriguing variation in Sheela theories.

Sam talks us through the Sheelas in Cashel and recommends a route starting at the Rock itself, then Bóthar na Marbh (the path of the dead) to Hore Abbey for the best framed view of the Rock, a detour round the fairy ring, then back into town for a drink at the Palace Hotel where we can see an indoor Sheela up close. While we’re in the tourist office, he shows us the vellum decree and beeswax seal that made Cashel a city back in the day, a political and ecclesiastical centre of power that could set its own laws and raise its own taxes. Sam recommends the tour at The Rock which starts on the half hour every hour but we’ve just missed one so he walks us to Cashel Folk Village to pass the time.

At Cashel Folk Village, “Sheelas have taken on a new meaning in today’s world and now represent liberated women. Sheela is seen through modern eyes as being ‘defiant’ rather than ‘deviant’.”

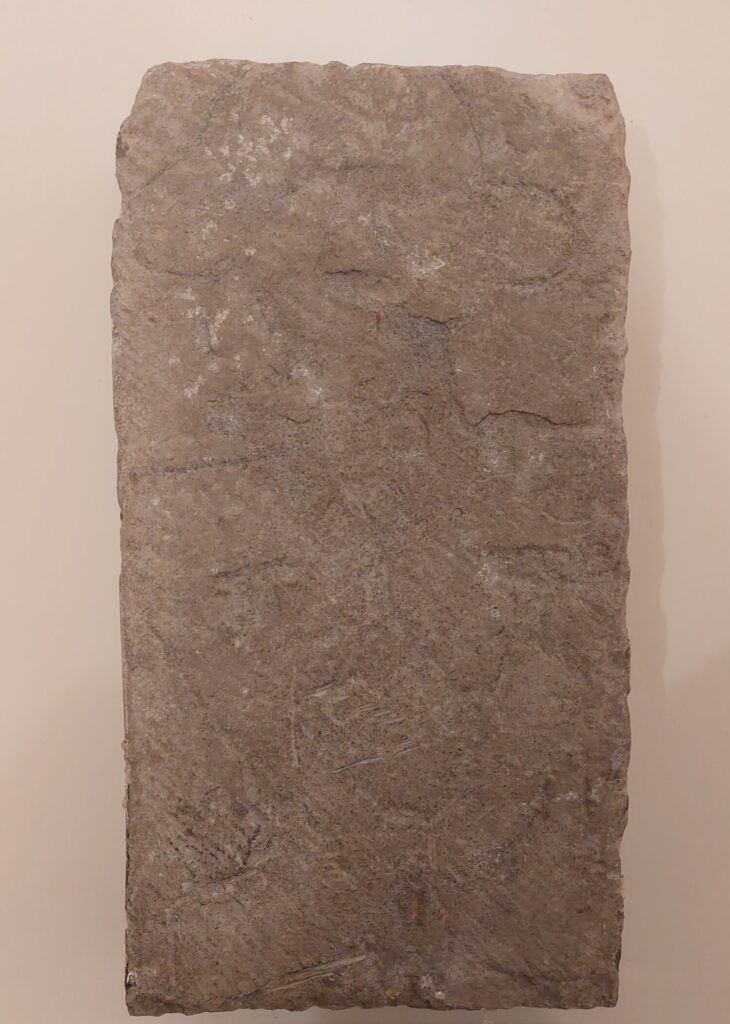

This quirky thatched cottage is stuffed full of memorabilia from prehistoric times to the War of Independence. It is the preserve of guide Bernard who is the son, grandson, great-grandson (possibly even great, great grandson) of the caretakers of the Rock of Cashel. His relatives still live in its caretaker’s cottage and work as guides and shopkeepers at the Rock: three centuries of guardianship. The Folk Village is also the home of a Sheela na Gig that isn’t on the map. As a tour of bored secondary school kids winds down, we take the opportunity to ask Bernard but he won’t be drawn on whether she’s an original or a replica. A previous Sheela in his keep was commandeered by the National Museum under Garda escort and now sits moldering in its archives, unavailable to the county she came from. He has some harsh words for the policies of the National Museum and for this reason, if anyone asks, the Sheela is a replica. To our eyes, she is too modern and unweathered and is likely a stylised version of the Rock of Cashel Sheela. She’s gorgeous nonetheless and we enjoy Bernard’s information boards, which acknowledge the theories surrounding Sheela-na-Gigs but suggest that they were carved on churches to repel evil spirits, as nakedness was seen as evil in Medieval times. “However, Sheelas have taken on a new meaning in today’s world and now represent liberated women. Sheela is seen through modern eyes as being ‘defiant’ rather than ‘deviant’.”

Realising the time, we leg it up the hill to the Rock and join the tour. Despite its name, the Rock of Cashel is not a castle but a cathedral with the official title of St Patrick’s Rock. Our guide David does a brilliant job of bringing to life the experience of a Cistercian monk living on the top of a hill in an Irish winter. He spans decades of the Rock’s history as a political site where the Kings of Munster or South Ireland ruled from around the 4th century to when they ceded power to the church, who leveled the existing wooden structures and quarried into the rock to build this stunning Cathedral by hand. Some of the rocks used for construction are from 16 miles away which would have been transported through thick forests. The Rock is surrounded by eight abbeys within an eight mile radius and locals could be called by a bell, one for worship and one for defence. The round tower is one of only 13 with its original pitched roof as most have been hit by lightning. Round towers are a uniquely Irish feature, as only two such towers exist elsewhere in the world, both in Scotland. The first act of the Board of Works (now OPW) on taking ownership of the Rock was to put a lightning rod on the tower. It was struck by lightning just two years later. The rod worked!

The site has an impressively intact Romanesque sandstone chapel, a gothic central cathedral, the round tower and a square castellated building, the bishop’s house, built for defence of valuable artefacts and important people. It could be reached via secret routes in the walls of the cathedral. The height of the cathedral’s vaulted ceiling is the result of a competition across Europe to see who could build the highest and therefore closest to God. The height of bishops’ hats also signified this and they competed to show how close they were, with hats up to 1.5 metre high. Cough *phallic* cough.

The Rock of Cashel Sheela represents a small feminine presence in what is otherwise an exclusively male history.

Bernard had given us a tip for spotting the Sheela and as we stood on the ramparts at the end of the tour we tried to make her out. She eventually came into focus. lying on her side with her head on the left edge of the wall and her legs pointing towards the window. We ask David and he draws the attention of the group to her and describes her as “an ancient fertility symbol”. She represents a small feminine presence in what is otherwise an exclusively male history.

After a cake stop at Granny’s we head down Bóthar na Marbh, the path on which the dead are still brought to be buried at the Rock. While Hore Abbey is clearly visible, the route to it is more roundabout unless we go cross-country so we get a grand stretch of the legs. We don’t find the perfect view promised by Sam but the Abbey itself is impressive. If it wasn’t overshadowed by the rock it would be more of a draw in its own right. Originally it had been a Benedictine order but they were busted because a Cistercian archbishop had a dream that they were plotting to murder him!

From here we set off and try to find the fairy ring that Sam has drawn on a map and which David told us to walk around clockwise three times. We approach it from the wrong angle and find a field of bullocks staring at us so we scramble back down the embankment of the M74 and walk around the corner, climb over a gate, temporarily disable two electric fences with a jacket, navigate a field of cow pats and then limbo under two more fences before coming up on the fairy ring, a circular, raised embankment protected by tall trees and brambles. It is eerie, dark and silent. Whether it has some supernatural significance or it was a regular ring fort which humans have imbued with their storytelling over the centuries, it has a powerful energy which wasn’t coming from the fences (though honorary gee Niamh did manage to get zapped). We set off in a clockwise direction on the outer ring but are soon forced by fallen trees and brambles to walk along its ridge. Hawthorns, also known as fairy trees, are determined to force us closer inside but we persist along our route. After one circuit we decide we’re not going to risk anymore. Brambles are attacking us everywhere we go and we daren’t enter the ring itself. One clockwise circuit is enough for us.

Returning towards the town, we remember one of the guides telling us about a ducking pond where “ladies of ill repute” were punished. We stop a local for directions and he tells us it was called the Gouts when he was growing up. He knows the history of it being used to punish women, whether by ducking for a short time or drowning he’s not sure, and his excellent directions take us straight there. It’s now part of St. Declan’s Way and is denoted with carvings of animals and symbols including, we’re delighted to discover, a replica ex-Sheela. Previously regarded as a Sheela, the original is now thought to be a Cat Goddess and can be seen in the museum on the Rock. She is in fact a carytid, intended as a supporting function on a building, and being armless is unable to reach her vulva for the classic Sheela pose.

The Gouts pool was used as a ducking pond for “punishing ladies who were found guilty of unsociable behaviour”.

The pool itself is almost completely grassed over and the small wooded area is obviously used as a drinking den by local youths. The information board here says it was used for “punishing petty criminals” but the board across the road at the Bóthan Scoir thatched cottage says it was for “punishing ladies who were found guilty of unsociable behaviour”. While this was a common punishment for women in medieval Britain, it was unusual in Ireland. The Gouts Pool dates to the 1500s but we can’t find a source on its use for ducking.

The Cashel Palace was originally the Bishop’s Palace but is now a Blue Book hotel and very posh. It was recently restored and has reopened after being closed for seven years. It’s beautifully done and it houses a Sheela in its basement. We are directed by the receptionist to the Guinness bar where we ask for the Sheela but the young bartender points to a group of older ladies in a corner, assuming we’re looking for someone named Síle. So we wander around and ask people until we find her on the wall of the corridor, very weathered and brightly illuminated. This makes getting a photo without shadow fairly challenging. We put a jacket over the brightest light. Her provenance is “unknown” but she’s genuine. According to Jack Roberts, she was originally in the Diocesan Library.

What’s interesting is that she’s described here more accurately here than at the Folk Village or the Rock; dated to 11th to 14th century and acknowledging the different, disputed meanings of the Sheelas. It concludes “whichever story you choose to believe, centuries later Sheela na Gigs are still regarded as powerful symbols and they add yet another dimension to Ireland’s cultural past”. We can’t disagree with that. Incidentally the Cashel Palace Hotel serves a perfect half pint of Guinness in a proper mini pint glass and we may have been tempted to stay for one or three in the comfy armchairs beside the fire. Sláinte!

*Author’s note: during term time, as we’re all educators of one sort or another, finding the time when we can all adventure at the same time is tricky, so some of these trips may contain fewer than the three original gees, or the odd honorary gee to make up the numbers.

Bibliography

McMahon, Joanne and Roberts, Jack (2001). The Sheela-na-Gigs of Ireland and Britain. Mercier Press.

Roberts, Jack (2018). Island of the Sheela-na-Gigs. Bandia Publishing.

Roberts, Jack (2009). The Sheela-na-Gigs of Ireland, an Illustrated Map and Guide. Bandia Publishing.