Day Three: We need to talk about William

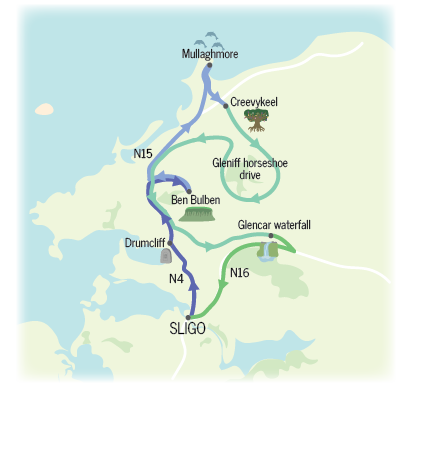

While this blog is dedicated to all things gee-related, it is impossible to visit Sligo and fail to notice the (very male) William Butler Yeats vibe. It was an irritating counterpoint to the amazing female energy of the rest of the trip. He was undoubtedly one of Ireland’s greatest poets, founding The Abbey Theatre and winning the Nobel Prize and all, but there’s a lot about Yeats and his personal life that made us feel icky. Here are some of the reasons why:

1. He wouldn’t take no for an answer from Maud Gonne. Having been rejected multiple times before she married 1916 rebel leader John MacBride, Yeats waited barely six months after MacBride’s death to ask her again.

2. Less than two years after his last proposal to her mother, he asked Maud’s daughter Iseult to marry him. She was half his age. And he had known her throughout her childhood (the poem To a Child Dancing in the Wind is about her).

3. Within two months of this refusal, Yeats married Georgie Hyde-Lees – another young one half his age – but spent their honeymoon brooding over Iseult.

4. He was a controlling fecker who changed Georgie’s name because he didn’t like it. He called her George.

5. “She stands before me as a living child” – his poem Amongst Schoolchildren sees him ogling a schoolgirl because she bears a passing resemblance to, you’ve guessed it, Maud Gonne.

6. His attitude to Indian poet Tagore, whose translated work he had helped to popularise in Britain, was problematic to say the least. When Tagore started writing poetry in English, Yeats claimed “no Indian knows English”.

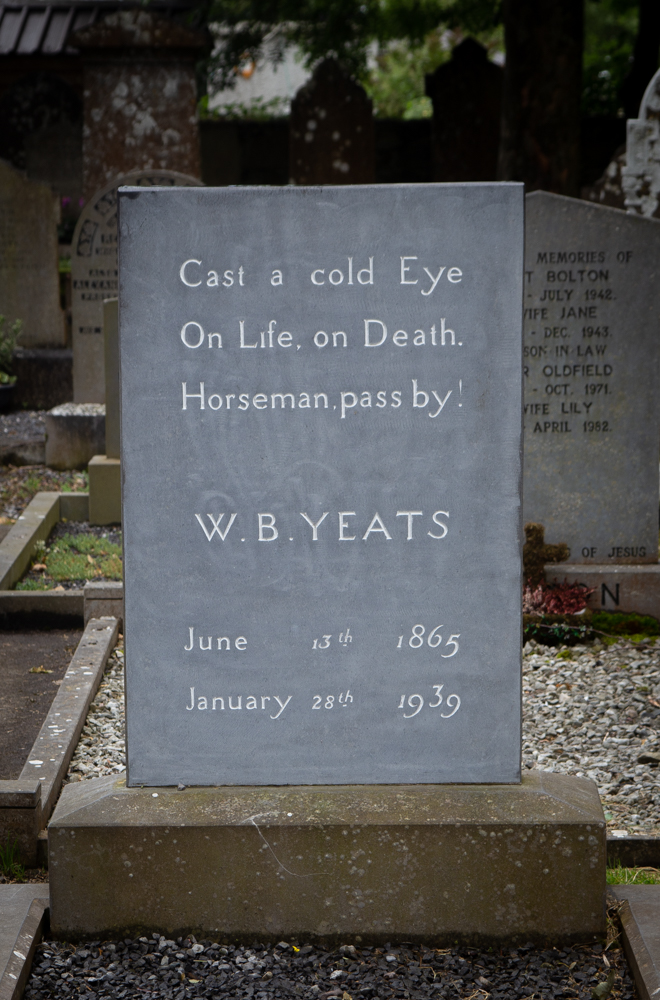

7. He left strict instructions for his gravestone, which failed to mention his wife or children. Poor Georgie is acknowledged with a plaque, bearing just her name, at the foot of his grave.

8. He was an actual wanker. Our friendly local, Darren, helpfully pointed out that the bronze sculpture on Stephen Street immortalises a hand in his pocket that’s definitely up to something. Kudos to sculptor Rowan Gillespie.

In Ireland, it’s difficult to find information on Yeats that isn’t hagiographic, and at school we were taught about his ‘love story’ with Maud Gonne as if that obsessive behaviour was romantic. But in the age of #MeToo someone needs to revisit this shit.

Our hotel was just up the road from Drumcliff so we decided to visit, if only to (metaphorically) spit on his grave. We didn’t – his wife and son are in there and it turns out that he may not be (his remains were returned from France after WW2 and may or may not be those of a French dentist). While the view of Ben Bulben from the churchyard is spectacular, we didn’t have the feeling of being in a ‘thin place’ that we’d had pretty much everywhere else we’d been on the trip.

Were Sheela-na-gigs a reminder to men of where they came from so they didn’t get notions?

We went into the Teach Báin gift shop for a wander (and a free pee) and discovered that Jack Roberts, the author of The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland and Britain and the map we were using to plan our search for them, was giving a talk there – the day after we were to leave. It was the first time serendipity had let us down and we gave some consideration to staying an extra night but we’re all working mammies and had other commitments, so we had to let this opportunity go. We did buy his book though, and had a chat with the shop’s owner about Sheelas. His theory was that they were a reminder to men of where they came from so they didn’t get notions.

Bibliography

Island of the Sheela-na-gigs, an illustrated guide. Jack Roberts (2018). Bandia Publishing and Design.

The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland, an illustrated map and guide. Jack Roberts (2009). Bandia Publishing, Galway.