Smashing, striking and rising: some commemorated women

We get off the bus on Lord Edward Street and begin this Wild Gees trip with a run down the 40 steps to the back of Dublin Castle. Sinéad says if we do this three times, the devil will appear (so her Dad told the tale). Gill’s version involves doing it with eyes closed (as her Mam claimed). Miriam’s parents are culchies so she looks uncomprehendingly from the top of the steps as we career down them. The devil does not appear.

We are in search of a plaque that commemorates the smashing of Dublin Castle’s windows but no one seems to know where on the castle this exists. We approach a security guard who looks confused at our request but gives it his best guess and leads us straight to it. It’s not looking its best just now, surrounded by scaffolding at the back of the castle, on the outside wall beside the gate. If it hadn’t been pointed out, we would have missed it. But this plaque marks the spot where Hanna Sheehy Skeffington “a rinne smidiríní” of these windows in the name of women’s suffrage.

Hanna is a Wild Gees fav for many reasons. She founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League in 1908 with her pal Margaret Cousins. She was a nationalist but also a pacifist. She and her other half Francis were so feminist they took each other’s surnames on marriage, becoming the Sheehy Skeffingtons. They set up a newspaper, The Irish Citizen, to promote the causes of universal suffrage, labour rights and Irish self-determination “for men and women equally”. Initially edited by Francis and James Cousins, Hanna took it over when Francis was shot during the 1916 Rising (we’ve posted before about her role as an Easter widow). Incidentally, the Wikipedia article for the Citizen didn’t give Hanna her props, so of course we had to edit it (see before and after below).

We were lucky to have excellent source material for the edit. In a bookshop wander a few days prior, we found Winning the Vote for Women by Louise Ryan, a wonderfully detailed account of the Irish Citizen and the suffrage movement in Ireland. We also stumbled across a treasure trove of the Dublin Historical Record and one of the volumes had an article on the Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association, which led us to the discovery of a memorial in Stephen’s Green dedicated to Anna Haslam and her husband Thomas “in honour of their long years of public service chiefly devoted to the enfranchisement of women”. Haslam was a quaker, a suffragist and founder of the Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association in 1874. Her name should be as familiar to Irish folks as Millicent Fawcett’s is in Britain. Her stone seat was the next stop in our trip.

So what’s the difference between a suffragist like Anna and a suffragette like Hanna? The suffrage movement in the 19th century had tried to achieve change through peaceful means, like petitions, letter writing and lobbying. Frustrated with the lack of progress after so many decades, the early 20th century saw a more radical approach of direct action, not-so-peaceful protests and property damage (like Hanna’s window smashing). The term ‘suffragette’ was coined by the British media to differentiate the militants from the more conservative suffragists.

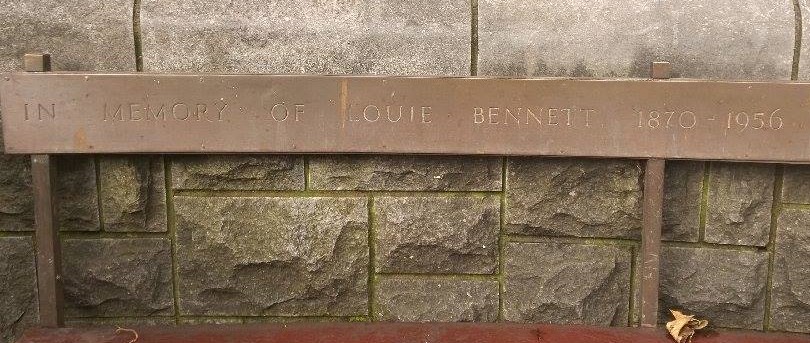

That wasn’t the only division in the suffrage movement. Some were fans of a universal suffrage which would extend the vote to every adult. At the time, only men over 30 who were property owners could vote, so many working class and younger men were also disenfranchised. There were others who only wanted the vote for ‘ladies’ like themselves. Many Irish suffragists were women of property while suffragettes like Hanna were often socialists or trade unionists as well. Louie Bennett, who we discover also has a memorial in Stephen’s Green while writing this post, founded the Irish Woman’s Reform League (IWSF) and was later involved in editing The Irish Citizen with Hanna. She was also involved in the Irish Women’s Workers Union with Rosie Hackett (more of whom later).

Another significant division in the Irish suffrage movement was between nationalists and unionists. Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond considered women’s suffrage something that should wait until after Home Rule. He also feared that, with so many protestants and women of means in the movement, that they would vote for unionist parties and hamper the cause of self-government. He aligned with the Westminster government to scupper the 1912 Conciliation Bill in order to gain support for the Home Rule Bill, much to the wrath of nationalist suffragettes. Sinn Féin weren’t much better, ruling the matter of suffrage out of order at its 1914 convention, when Hanna, Constance Markievicz and Jenny Wyse Power attempted to raise the matter. Some nationalists dismissed it as an “English campaign”. Unionist leader Edward Carson on the other hand, had (reluctantly) pledged to extend suffrage to women in a provisional government for Ulster in 1913.

It’s no surprise that so many of the nationalist suffragettes were involved in Cumann na mBan and the more militant republican movement. The 1916 proclamation of the Irish Republic contained the right to equal suffrage. In an editorial on the “suffrage casualties” of 1916, The Irish Citizen commends the commitment to suffrage of James Connolly particularly, “never a jibe at womanhood fell from his lips”. It mentions Pearse, MacDonagh, Plunkett and Clarke’s friendship to the movement and briefly name checks Mallin and McBride. In Margaret Ward’s biography of Hanna SS, she recounts a conversation between Hanna and Connolly, in which he tells her that equal suffrage is to be included in the proclamation and that “only one questioned it”. History doesn’t record who that one was, but if we assume that Hanna knew and was the author of the editorial, I think we can narrow it down. We’re looking at one of you, Seán MacDiarmada and Éamonn Ceannt.

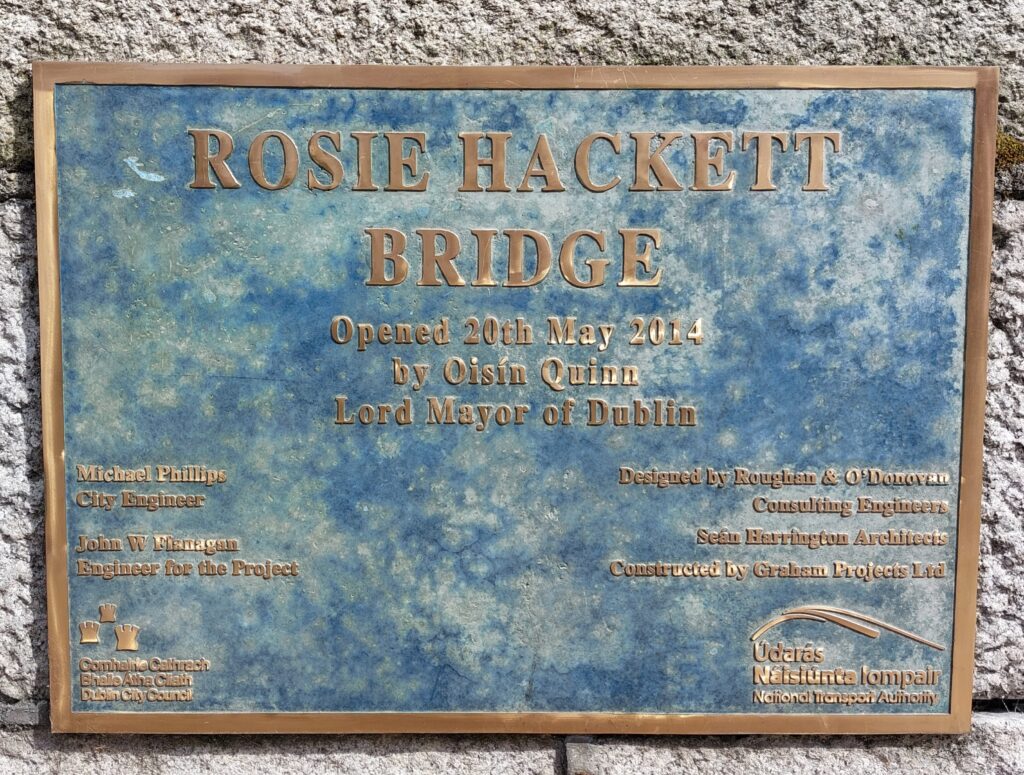

Our next stop brings us to the river Liffey, where one of Connolly’s comrades is commemorated. Rosie Hackett, one of the 77 women of the 1916 Rising, was a member of the Irish Citizen Army and a lifelong trade unionist. She co-founded the Irish Women’s Workers Union with Delia Larkin (sister of Big Jim) and helped mobilise the Jacob’s factory workers during the 1913 Lockout and set up a soup kitchen at Liberty Hall. In the preparations for the Rising, she was part of the group that printed the proclamation. Under the command of Countess Markievicz, Rosie provided first aid in the Royal College of Surgeons during the fighting. Several of the 77 women were also involved in the IWWU, including Helena Molony and Winifred Carney. Rosie continued her trade union work for more than five decades and was awarded a gold medal in 1970 by the ITGWU. Fittingly, this amazing woman now has a bridge named after her directly in front of Liberty Hall. It’s actually heart-warming to see the lovely plaque beside the bridge, doing justice to her legacy. Though it doesn’t escape our notice that no less than four men manage to get their names on it as well (the Lord Mayor, City Engineer, Project Engineer and Architect all get their names and job roles, there is no biographical information about Rosie).

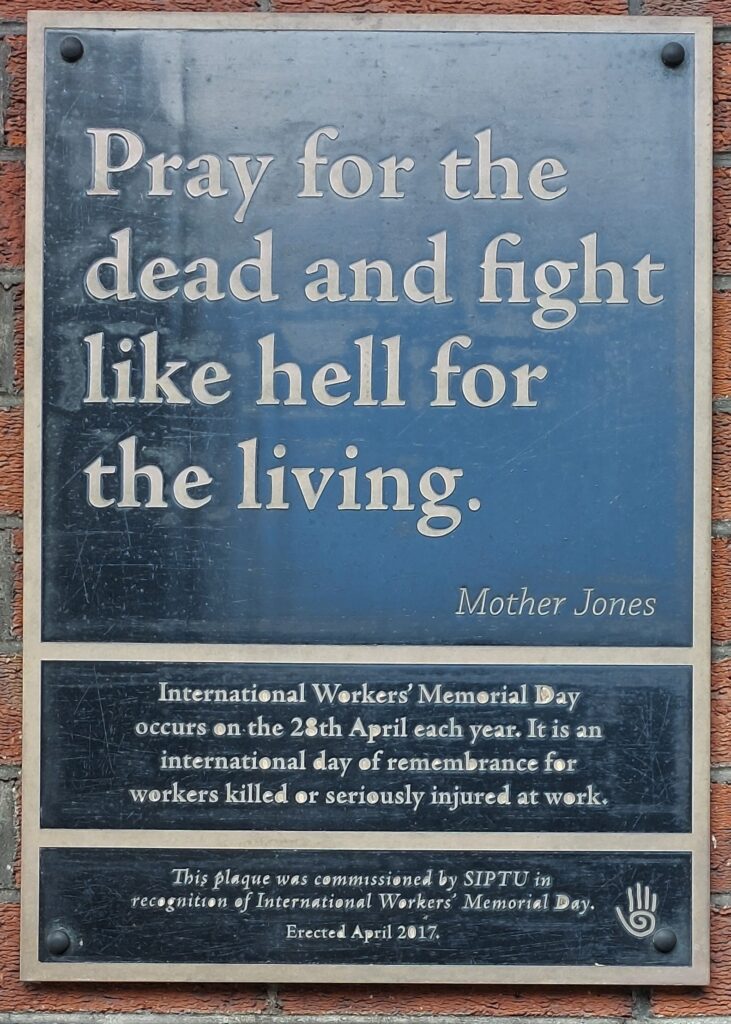

We cross over the Liffey and head to Liberty Hall, which features a plaque on its outside wall commemorating the Irish Women’s Workers Union and the 1945 laundry workers’ strike. It also features a quote from Mother Jones, born Mary Harris in Cork but who became a famous labour organiser in the US, “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living”. Jones was once known as “the most dangerous woman in America” and was instrumental in bringing in child labour laws but for some reason wasn’t a fan of women’s suffrage.

We could suggest going to nearby Connolly Station and hopping on a train to Belfast for our next find, but it didn’t quite happen like that. A few days later, one of us spotted this fabulous sculpture outside the Europa bus station on a non-gee-related trip (but women’s history is everywhere once you start looking). The Monument to the Unknown Woman Worker by Louise Walsh features two women with slogans and symbols of working, motherhood and the campaign for women’s rights embedded in their bodies – a typewriter here, a wrench there, a baby’s soother dangles from one ear, a clothes hanger across a back.

Belfast is also home to Mary Ann McCracken, anti-slavery campaigner and all round formidable woman. A statue of McCracken has recently been approved for Belfast City Hall, along with one of Winifred Carney, of 77 women and IWWU fame.

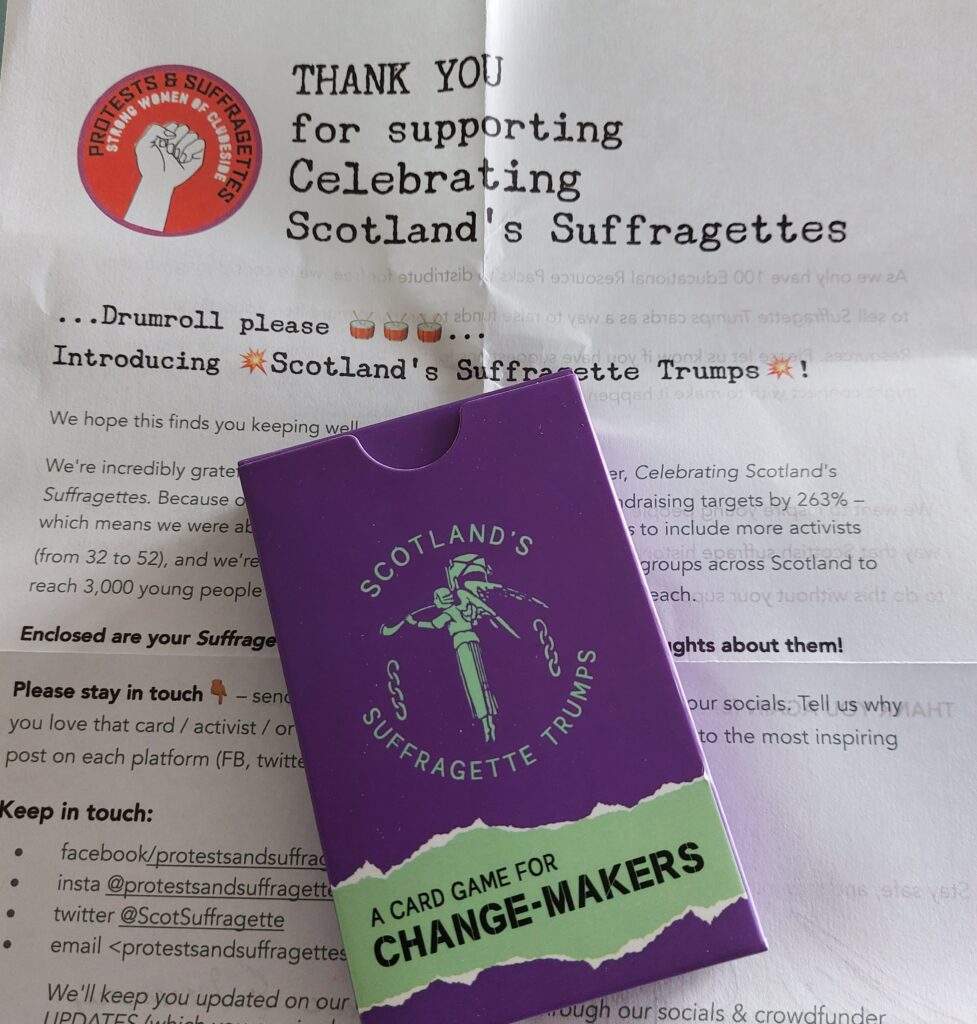

Just a ferry ride from Belfast are our pals, Protests and Suffragettes in Glasgow. They have recently brought out a set of Scottish suffragette top trumps cards, featuring among many others Irish suffragette Dolly (Mary) Maloney, who followed Churchill on the Dundee election trail in 1908, drowning out his speeches with a bell. You too can own a pack of these amazing cards but hurry as stocks are limited. Proceeds will fund education packs on women’s suffrage for schools across Scotland.

Since we started this blog, we have been pretty clear that Wild Gees feminism is intersectional and inclusive of trans women and non-binary people. We have recently become aware that while some amazing work is happening in Scotland to uncover women’s histories (we’ve mentioned some in previous posts: Protests and Suffragettes, Sara Sheridan’s Where are the women?, the campaign for a pardon for those persecuted as witches, Women in Red wikipedia editathons) there has also been a mobillisation of non-inclusive voices that call themselves feminist but seek to limit the rights of LGBTQ+ people. Sadly, they have co-opted the suffragette colours of green, white and purple on social media. We’ll continue to celebrate the achievements of the suffragettes (though not all of them were as sound as Hanna, Louie and Dolly) but want to be absolutely clear that we have no connection with, or tolerance of, people who are determined to define women by narrow biological functions.

Bibliography

Marie O’Neill (1985). Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association and its Successors. Dublin Historical Record. Vol XXXVIII, No.4. September 1985.

Louise Ryan (2018). Winning the vote for women, the Irish Citizen newspaper and the suffrage movement in Ireland. Four Courts Press.

Margaret Ward (2017). Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. Suffragette and Sinn Féiner. Her memoirs and political writings. UCD Press.

E. Sylvia Pankhurst (1931). The Suffragette: The History of the Women’s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905 1910. Reprinted 2019. Read Books.