The Wild Gees in Iceland

As this year marks the Wild Gees’ demi-siecle*, we realised a plan a long time in the hatching – a trip to Iceland to see the Northern Lights. Another long-held wish was to visit the Vagina Museum, so we flew back via London with this intention. This was the most planned in advance the Wild Gees have ever been (see all previous blogs with a recurring theme of last minuteness), with flights booked as far back as October 2022. So of course fate had to intervene. Did the northern lights appear? Did they feck. And even sadder, the Vagina Museum was evicted from their premises at short notice earlier this year and are still searching for a home. Despite these disappointments, we managed to have some adventures with a (mostly) women’s history theme.

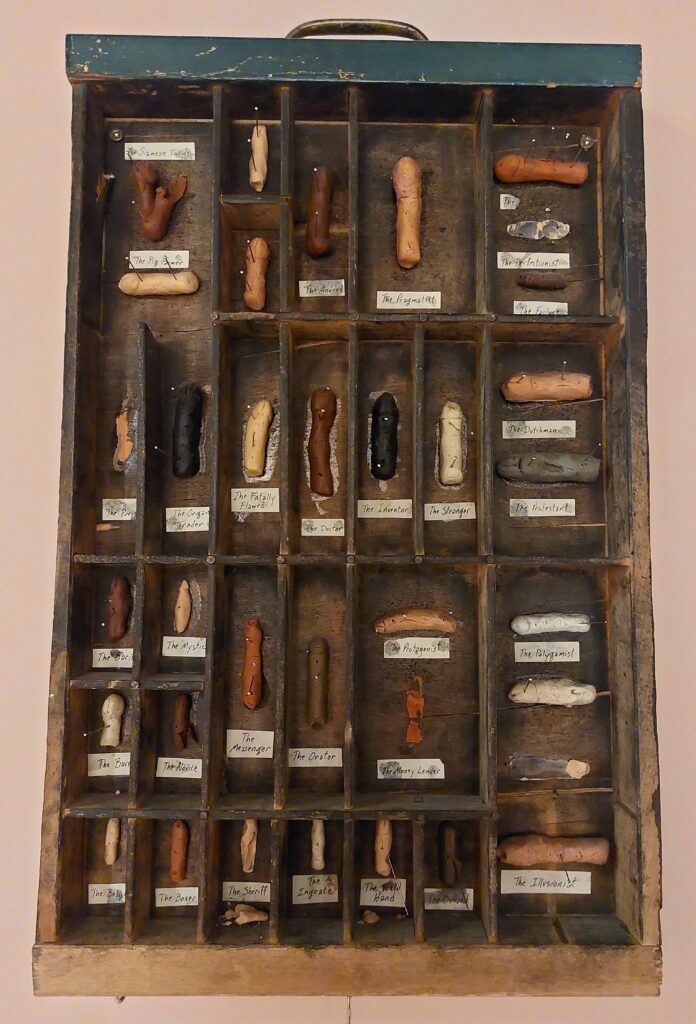

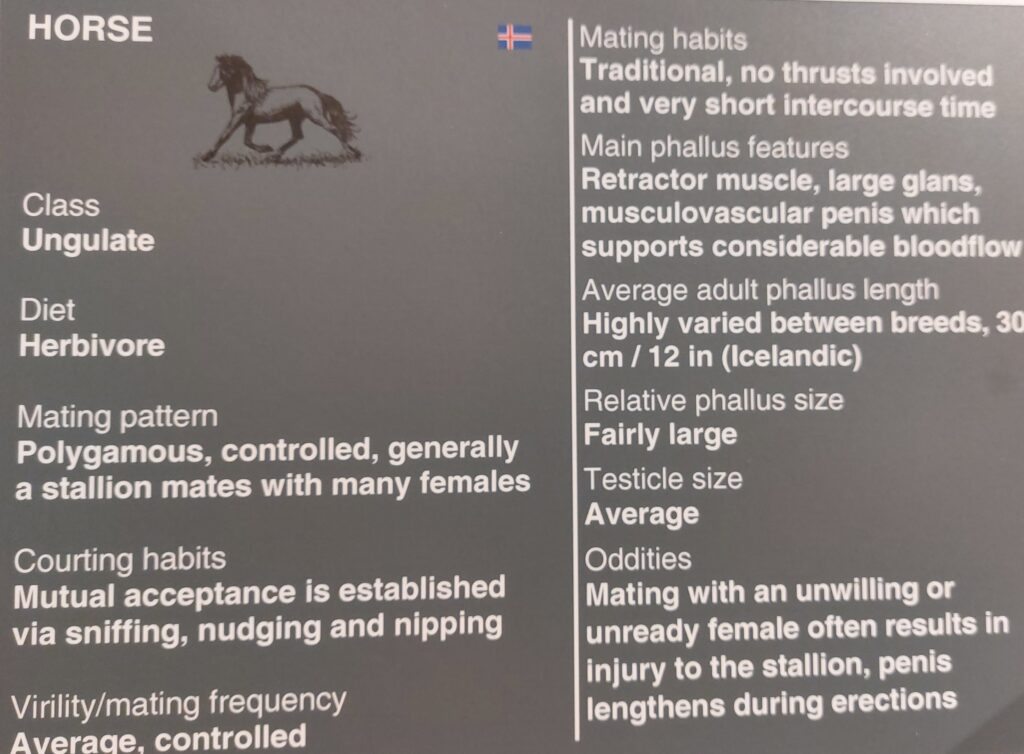

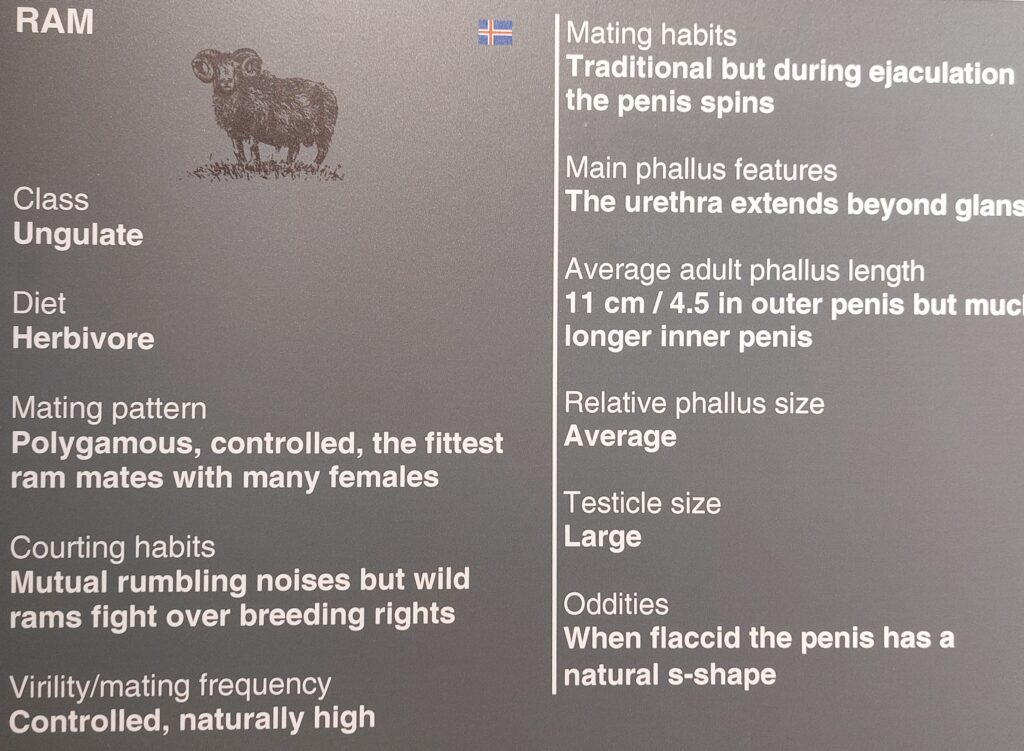

In a departure from our usual adventures, we visited the Penis Museum in Reykjavik. The plan had been to balance this with the Vagina Museum in London but that was not to be. The museum was like a dead zoo of penises, with each animal’s mating habits, penis length and girth relative to size. The horse and boar families did relatively well here but, having managed to anthropomorphize every species, we were disappointed to learn that a bear’s size is almost inverse to that of its penis. You’d have to settle for a lovely big hug.

By the end, we were swiping right or left on each of the profiles. The human section is relatively small, but people have donated their penises to the museum and there’s a cast of Jimi Hendrix’s willy. The long dark nights in Iceland have generated a bizarre cast of mythical creatures and each one’s peen is on display here. We won’t trouble you with the sight of the troll’s.

The invisible man’s penis is also on display, or not as the case looked pretty empty to us. In Icelandic folklore, he is one of the ‘hidden people’. It’s said that they originated in biblical times when God told Eve to line up her children before him and to make sure they were all neatly turned out. Now Eve had a shedload of kids and some were neater than others. So she shoved some of the scruffier ones into a cave while God was doing his inspection. Who hasn’t been there Eve love? He noticed that she was a few short and put a(nother) curse on her – that “what she had hidden from him would be hidden from her and all her descendants”. Harsh.

More than 62% of Iceland’s female genome is Celtic.

Ebenesersdóttir et al (2018)

Our second favourite museum was the archaeological Settlement Exhibition built around an excavation of a Viking longhouse. Iceland was uninhabited before being settled by the Norse around 870 CE (though 8th century author Dicuil claims there were Irish hermits there before). One thing the settlers were short of was women and they addressed that by raiding the coasts of Ireland and Scotland. With the result that more than 62% of Iceland’s female genome is Celtic. The museum’s interactive display boards describe this as ‘cultural affinity’.

In one of the Icelandic Sagas, there’s the story of Melkorka (Mael Curcaig), whose father was an Irish chieftain. She was captured and brought to Iceland as a concubine, where she had a son Ólafr. She raised the son with stories of her life as a princess in Ireland. When he grew up, Ólafr returned to Ireland and took his place in the clan, who were fierce impressed with his Irish.

While Icelandic culture draws heavily on Norse myths, it doesn’t have a history before 870, which felt strange to us. The other strange thing is the landscape. In Ireland we can point to geographical features formed millennia ago but some of Iceland’s landscape is much newer than that, being constantly formed and reformed by seismic activity. The landscape is full of black volcanic rock and frozen lava flows and it’s easy to believe that trolls inhabit it. Less easy to believe that humans have managed to survive and thrive here. Everyone we meet in Iceland is so friendly and seemingly happy. The secret? Vitamin D apparently.

Grindivik is one of the most seismically active parts of Iceland, and also surprisingly the happiest. It’s close to the rift where the Eurasian tectonic plate and the North American plate are moving away from each other. They have recently installed a bridge between the two continents, so you can cross from one to the other.

In April, the dark nights are rapidly receding and there’s a palpable sense of things coming back to life.

One of the reasons for the sprightliness of the Icelanders is the turn of the season. In April, the dark nights are rapidly receding and there’s a palpable sense of things coming back to life. There is construction taking place on every block of Reykjavik. Crocuses are popping up and the snow on the mountain view we wake up to from our hotel window visibly shrinks over the few days we’re there.

Sadly, it means the Aurora Borealis will become less visible at night. We took a boat trip out across the harbour and even at 10pm it felt like twilight. It was another hour before the sky felt properly dark. Though it was amazingly still and clear, the lights did not appear. Neither did Billy, the humpback whale who’d been seen in the harbour earlier that day. But we saw Venus cast its light in a perfect line across the water and vowed to come back.

Don’t feel too sorry for us. We also made a trip to the Blue Lagoon where we marinated in a soup of saltwater, silica and sulphur for four hours, until our bones had melted and we had to be poured back onto the bus. 10/10 would recommend. The lagoon is an expensive treat, but there are municipal thermal spas all over Reykjavik. The City Card gives you free access to all of them, plus city buses and museums (the Penis Museum is not included but you get a discount).

Our hotel was near a spa so we took full advantage. On the way there through Laugardalur park, we passed the site of the city’s laundry. Women once washed clothes at the hot springs here, which for many years were dangerous due to slippery banks and bursts of steam. Three women lost their lives before safety rails were erected in 1902. There are information boards telling the story of the laundry women and a beautiful statue commemorating them by local sculptor Asmundur Sveinsson.

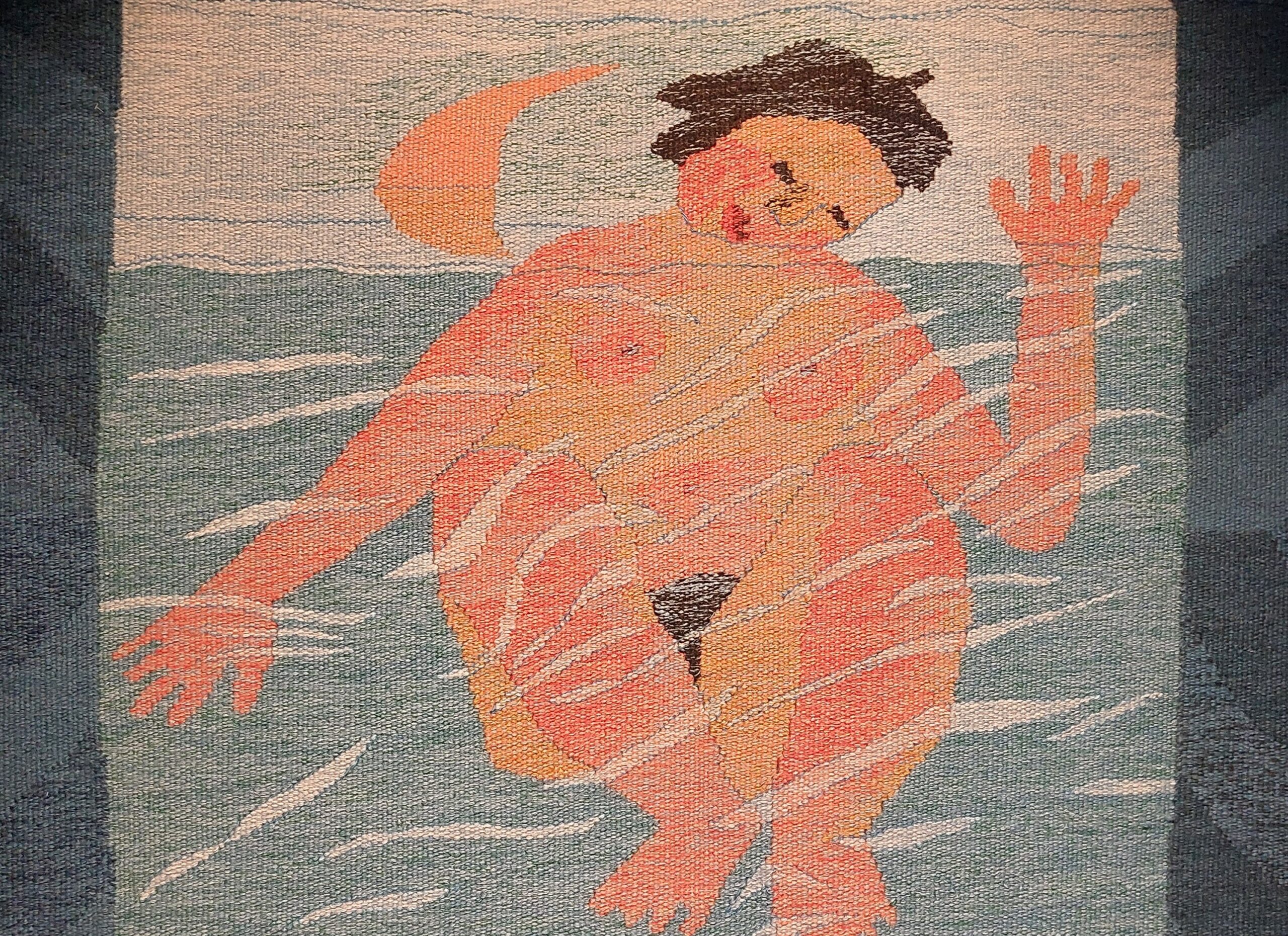

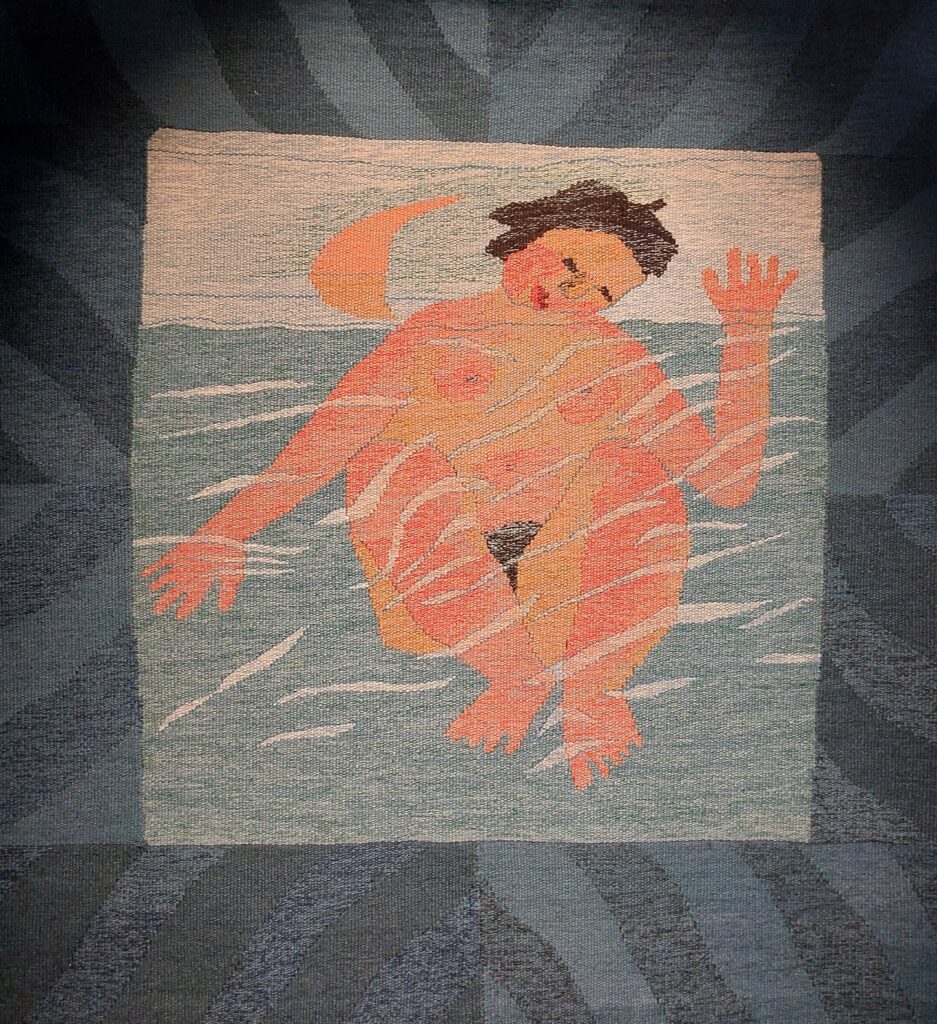

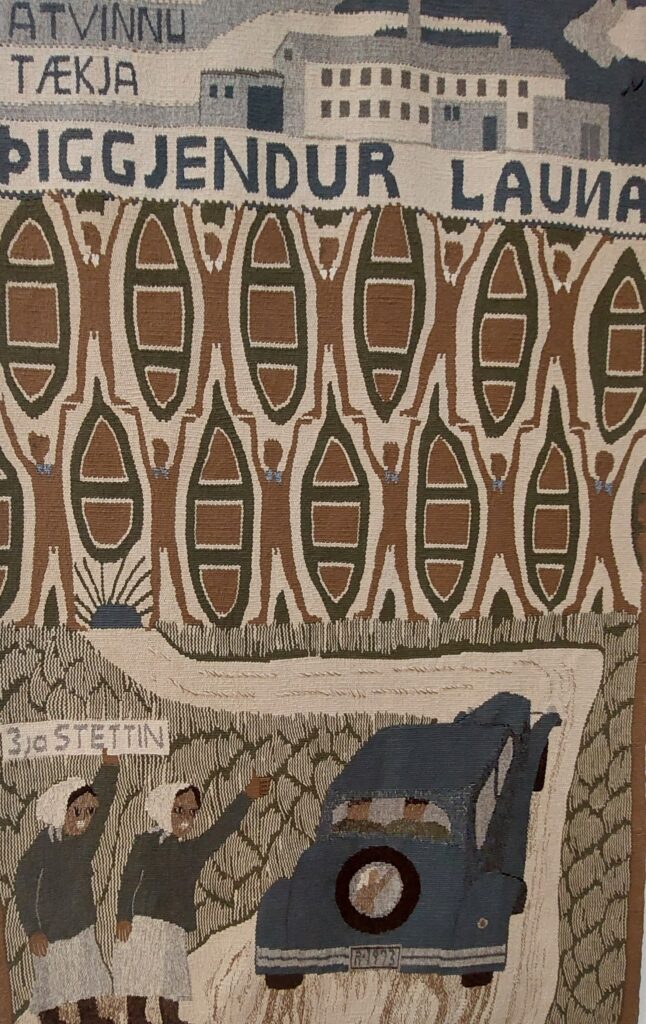

We also used the card to tour the city’s galleries and discovered Hildur Hakonardottir, a textile artist who used tapestry to convey messages about gender politics, drawing on the history of women’s crafting of textiles. She was instrumental in the 1975 Women’s Day Off, when Iceland’s women went on strike for equal pay and won. We are very tempted to create a Wikipedia page for her. On our last day, for a blissful moment, we found ourselves alone in a beautiful old library. It had an index cabinet in which you are invited to catalogue your name, the date and your wish for the future. Bless** Iceland, the Wild Gees will return.

* nicer than saying we all turned 50 ** Icelandic for Bye

Bibliography

Elves and the Hidden People, Twelve Icelandic Folktales. Almenna bókafélagió (2022)

Ebenesersdóttir et al (2018). Ancient genomes from Iceland reveal the making of a human population. Universitetet i Oslo. (p2) https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/10852/71890/2/aar2625_CombinedPDF_v1.pdf

The Sagas of Icelanders. Penguin Edition (2005)

The Reykjavik Grapevine (2019). Grindavik: The Happiest Place In Iceland. https://grapevine.is/travel/2019/04/16/move-over-disneyland-grindavik-is-the-happiest-place-in-iceland

Photos: all by the Wild Gees CC-BY-SA, except Hildur Hakonardottir images, Reykjavik Art Museum