On the hunt for Sheelas, old and new

The Papal Cross in the Phoenix Park may seem an unlikely place to go Sheela hunting, towering phallic symbol of the patriarchy that it is, but we had been given a tip off about a guerrilla Sheela and we were investigating. We regret to report that we found no trace of it, despite searching the site of the cross and the surrounding area pretty thoroughly. It was a disappointing start to our first Wild Gees trip in over a year but it got us thinking, not just about who erected the Sheela in the first place, but who removed it.

We can’t say much about the project (though we’re hoping to bring you an interview soon), but it was deliberately anarchic so there is no definitive list of sheelas. The intention is for people to stumble across them rather than hunt them as we tried to do. We can definitely say that the one in Grangegorman is still there and has been added to the map of Sheela na Gigs. This was the only one we found, of potentially hundreds across Dublin. We had no joy at the Abbey Theatre (another tip off). We asked a guy who was running an antiques shop in the lane beside the Theatre if he knew anything about the Sheela. This prompted him to share his many, usually accidental, encounters with Sheelas over the years. Most of them were in Tipperary, a veritable hotbed of Sheelas that we really need to plan to trip to, but also on pilgrimage in Santiago de Compostela, where he came across a Sheela and a lesser spotted Seán na Gig.

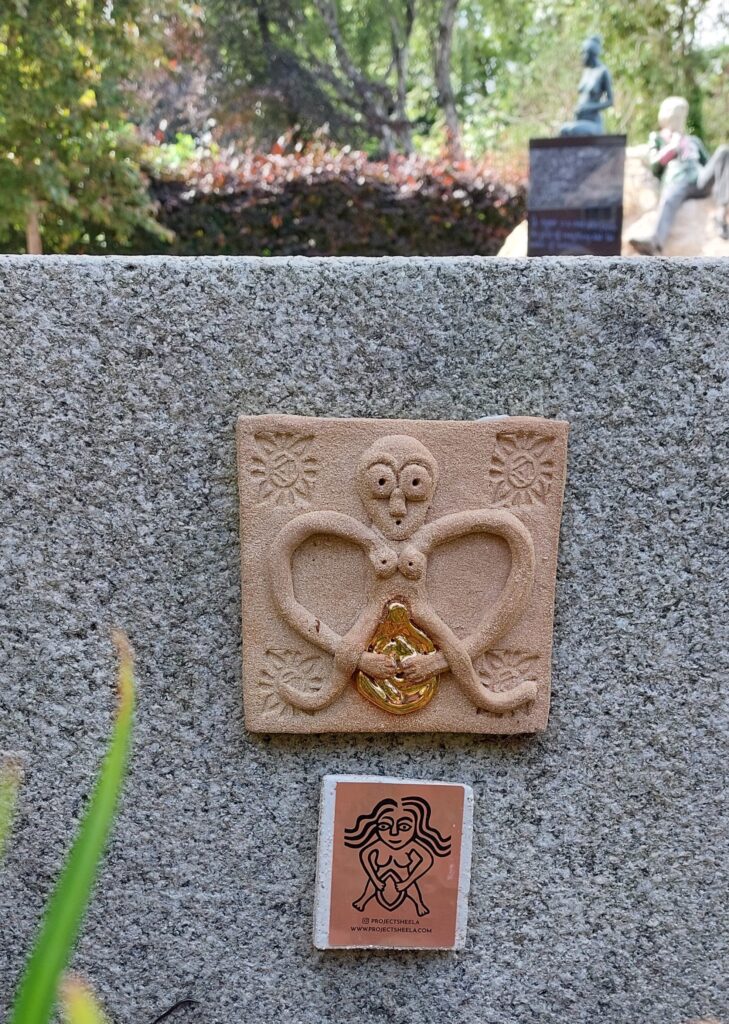

More recently, a Dublin-based street art project called Project Sheela was set up to mark International Women’s Day in 2020 and again in 2021. Unlike the guerilla Sheelas, which are concrete casts, Project Sheelas are ceramic and couldn’t be mistaken for the real thing. They have also helpfully listed all the locations from both years on their website. Unfortunately, some of these are now missing too. We were delighted to find the one in Merrion Square, next to Oscar Wilde’s statue, commemorating his mammy Lady Jane (aka poet and nationalist Speranza). It is in a cleverly hidden – so less likely to be removed – place behind a nearby bench.

We were less lucky at Neary’s Pub on Chatham Street. This Sheela was erected to mark a feminist protest in 1976, when Nell McCafferty led a group of women into the pub and ordered a brandy each. When one woman ordered a pint and was refused service (as was the norm at the time), they all drank their brandies and left without paying. Though the member of staff we spoke to had heard of the McCafferty incident (and claimed she has since forgiven them), he had no clue about the Sheela and pointed out that as a listed building it would have been difficult to surreptitiously place her on the facade. He suggested we email the management, which allowed us to ask if they had removed it, but they hadn’t heard of it either. We’d love to hear from anyone who knows the whereabouts of this and other Sheelas. We’re particularly curious about the motivations of the people who have removed the secret sheelas over the years. The ceramic sheelas could certainly have become collectors’ items and been prised off by fans. There’s also a long and not exactly proud history of Sheelas being considered offensive and many of the authentic sheelas have been removed or defaced over the years. Could this still be happening in 2021? Or have they been victims of the art police, objecting not to the Sheela but to her location in an ‘unsanctioned’ place?

Feeling a bit dejected after so many missed Sheelas, we aim for a sure thing. The National Museum has a substantial collection of Sheela na Gigs, at least one of which is on regular display. Not today though, as that gallery is currently being renovated and is roped off. But of course it is! Luckily for us, our new pal Harry took pity on us and snuck us in for an unofficial tour. Apparently we were the first people to ask about her in four years, though in fairness the last year has been a bit of a write off. The person before us was none other than James Bond (according to Harry, Daniel Craig is shorter than you’d expect but with piercing blue eyes – in case you were wondering). Usually it’s midwives and maternity nurses, from all over the world, who come looking for the Sheelas. So few Irish people show an interest that Harry asks how we know about them. It was this very question that prompted our Wild Gees adventures in the first place, but Sinéad and Gill are stumped. How did we know about them and Miriam didn’t? So we credit the fact that we’re from Crumlin, and had many a school trip on Bus Átha Cliath (or CIE as it was back in the day), three to a seat, to visit the many museums and heritage sites on our doorstep. Kudos to Mr. White, our geography teacher and all round legend.

As is now traditional, we ask Harry for his Sheela theory. He reckons they were for protection, specifically of women during childbirth at a time when maternal mortality was high. We hadn’t come across that idea before but now that we think of it, many of those gees are pretty stretched. How dilated are those Sheelas’ cervixes?

When we come face to face with the mighty Clonmel Sheela, we are agog. Having seen so many Sheelas in situ, weathered almost beyond recognition and often so high up as to be inaccessible, it’s a shock to see one up close and so well preserved, with intimidatingly ugly features and several fingers firmly inserted in her gaping vulva. Obviously, we LOVED her. This is a dilemma for those charged with protecting our heritage: is it better to take the Sheelas indoors for conservation, and so we can experience them intact, or leave them in the wild, so we can better understand their original context but where they are exposed to the elements. Incidentally, the information board says Síle na gCíoch – Sheela of the breasts – but we prefer Síle na Gídhe (gee).

Harry spoke of the uniqueness of some of our ‘stone’ heritage. While pride of place in the museum goes to the stunning metal artefacts of Irish history and prehistory, he would like to see a dedicated, permanent display of Ogham stones and Sheelas so more people are aware of them. There are a shedload of Sheelas in the museum’s collection that are rarely displayed but Sinéad reckons she could justify asking the duty curator for access as part of her PhD studies. Watch this space!

We had a deep chat with Harry about how recently in our lifetimes many misogynistic and stone-hearted religious practices had ended. Though the ‘churching’ of women after childbirth was officially ended in the 1960s, all of our mothers had been churched after we were born a decade later. The refusal to christen stillborn babies only ended in the 1990s, leaving a network of cillíní around Ireland – areas of unconsecrated ground where bereaved parents buried their children – and the concept of ‘limbo’ was finally, officially abandoned by the Catholic church in 2007.

On our way out we pass through the Egyptian room and Harry points out the collection is a bequest from a Lady Harriet Kavanagh, a member of the Irish privileged classes who instead of the more traditional 19th century tour of Europe opted to take part in Egyptian excavations and took home some artefacts as souvenirs. The fact the museum has them is a legacy of Ireland once having been part of the British Empire. As we are discussing the contemporary ethical implications of this, we are plunged into darkness. Harry blames the old building’s faulty wiring, we know it’s a curse. Give them back!

In the Museum shop, we find some new Sheela jewellery, a large depiction in white bronze of the Rahara Sheela from Co Roscommon. It is by Bandia Designs and Jack Roberts, author of some of the definitive texts on Sheelas and the map we used to plan our first trip. We buy one each, of course.

Later, we make a mad dash out to Malahide Castle to see a Sheela in the wild, and are caught in torrential rain. This is both a curse and a blessing. We discover that only family members of people buried there can enter the locked grounds of the Abbey, on which not one but (possibly) two Sheelas sit. In theory they are visible from the perimeter but unless you have a very powerful zoom on your camera, taking a photo is pointless. So we may or may not have noticed two locals who seemed to know what they were doing, slip quietly through a gap in the wall. Using the cover of a convenient downpour, we may or may not have followed them for a closer look (much to their surprise as we suspect they were after a bit of alone time). Once closer, it is possible to make out the gable Sheela, but it is covered in lichen that is eroding the surface detail. The Sheela na Gig website notes that it has deteriorated substantially “since it’s ivy covering was removed” as photos show much more detail a few years ago. Another figure, which is better protected from the elements and has retained the detail of the face and upper body, has unfortunately lost its bottom half entirely. We’re assuming it once shared the characteristic Sheela parts as the shape is very similar to its conclusively Sheela counterpart. They are unusual as they are carved from red sandstone and set within a frame. We can’t help wondering if there is a compromise between taking all the Sheelas indoors or leaving them to their fate. Someone needs to devise a way to protect the wild Sheelas.

A few days later, in another downpour, one of us nips in to see the Sheela at Rath, Co. Clare on a family holiday. This one is a spectacularly acrobatic Sheela, placed accidently upside down when the decorated stone from the original church was moved into a more recent building. That building is now in ruins and being taken over by ivy, a famous destroyer of historic buildings (though apparently served a protective function in Malahide?). It is encroaching on the Sheela when we arrive so we do a quick rescue mission and remove all the ivy in the vicinity. A small gesture against a relentless foe. But she is gorgeous, and well worth the detour down increasingly narrow boreens to a dead end at Rath church. Its location on a small hill commands what would be amazing views of the surrounding countryside in better weather. We wonder if Rath is a possible ‘node’ site, built on layers of sites of spiritual significance. If it wasn’t for the weather and a disgruntled child, we would have stayed and explored more here and the nearby Sheela at Killnaboy. There’s a reason our Wild Gees trips are sans enfants.

Our trip into Ennis to see a Sheela in the museum is less fruitful. The museum is closed for renovations as they make space to move De Valera’s presidential car into it. You’d think Dev’s days of thwarting women were over. We find the car later beside the library. We are not impressed. If you’re in Ennis though, pop into Scéal Eile on Upper Market Street. We were drawn in by the window display featuring the beautiful cover of Wild Gees fav Doireann Ni Ghríofa’s new poetry collection To Star the Dark. Not that we need an excuse to visit a bookshop. Doireann’s book features a poem about Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, author of Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire and auntie of the bould Daniel, and her search for Eibhlín’s grave – At Derrynane, I Think of Eibhlín Dubh Again.

“If I could find your gravestone,

I’d bring no rose, Eibhlín,

only a fistful of myrtle stems

tied in twine, tugged tight

and neat, to be placed,

gently, at your feet.”

The original artwork the cover is taken from is by Tom Climent and hangs in The Old Grand Hotel on Station Road, so you can pop in and view that and maybe have a pint now we’re allowed.*

*Covid guidance in August 2021. Can’t guarantee you a pint if you’re reading this later in the year!